X

Photo:

Juneteenth day celebration in Texas. 1900.

Juneteenth is one of the most important events in our nation’s history. On “Freedom’s Eve” or the eve of January 1, 1863 the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect.

At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in the Confederate States were declared legally free. Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom.

But not everyone in Confederate territory would immediately be free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was made effective in 1863, it could not be implemented in places still under Confederate control. This meant that in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later. On June 19, 1865 that changed, when enslaved African Americans in Galveston Bay, TX were notified by the arrival of some 2,000 Union troops that they, along with the more than 250,000 other enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree.

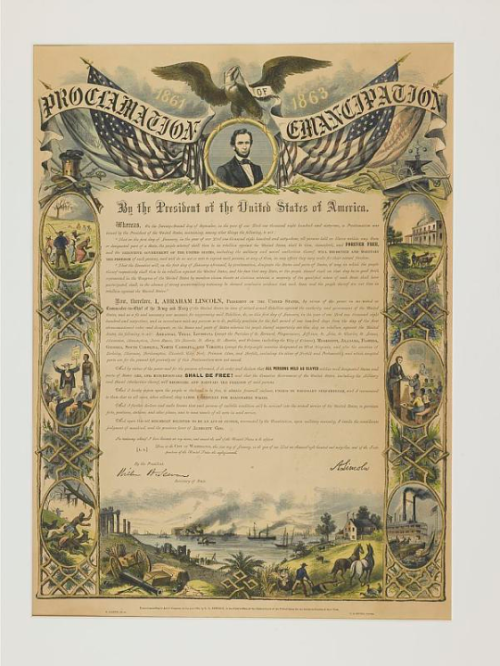

Photo: Publishers throughout the North responded to a demand for copies of Lincoln’s proclamation and produced numerous decorative versions including this engraving by R. A. Dimmick in 1864. National Museum of American History, gift of Ralph E. Becker.

The post-emancipation period known as Reconstruction (1865-1877) marked an era of great hope, uncertainty, and struggle for the nation as a whole. Formerly enslaved people immediately sought to reunify families, establish schools, run for political office, push radical legislation and even sue slaveholders for compensation. This was nothing short of amazing! Not even a generation out of enslavement, African Americans were inspired and empowered to completely transform their lives and their country.

In my opinion, Juneteenth (as that day was called by the freed enslaved people in Texas) marks our country’s second independence day. Though it has long been celebrated among the African American community it is a history that has been marginalized and still remains largely unknown to the wider public.

The historical legacy of Juneteenth shows the value of deep hope and urgent organizing in uncertain times. The National Museum of African American History and Culture is a community space where that spirit can continue to live on – where histories like this one can surface, and new stories with equal urgency can be told.

Tsione Wolde-Michael is the Writer/Editor for the Office of Curatorial Affairs, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. She is also a Doctoral Candidate in History at Harvard University.

Photo: The steeple of Emanuel African Methodist Church, Charleston, SC by Spencer Means, WikiMedia Commons.

We at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) are deeply saddened by the shooting deaths of Rev. Clementa Pinckney and his fellow worshipers at the Emmanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina, last night as they attended Bible Study. We are shocked by this murderous act that took the lives of so many. All of us here at NMAAHC offer our deepest condolences to the family and friends of those senselessly slain, and to the people of Charleston, we impart our most heartfelt thoughts and prayers.

Emmanuel A.M.E., one of our nation’s oldest historically black congregations, has long stood as a symbol of freedom in the south. It has been the gathering place for African Americans in peaceful worship and social activism since its inception more than 200 years ago. The church has played host to numerous peaceful Civil Rights advocates including Booker T. Washington, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins and Coretta Scott King, among others.

I reached out this morning to my friend, Joe Riley who is the Mayor of Charleston and shared our condolences. This violent act – the slaughter of innocents based on hatred, bigotry and ignorance – reveals the importance of the museum’s work. At the museum, our goal isn’t only to collect objects and stories, but also to combat ignorance. Through our work, we endeavor to build a healing bridge of hope between our tortured racial past and a future of peace and solace for all Americans.

Please join us in continuing to keep those who are suffering in your thoughts and prayers.

Lonnie Bunch

Founding Director

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Photo:

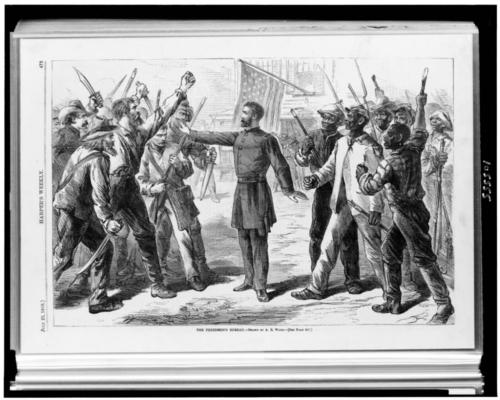

A Bureau agent stands between armed groups of whites and Freedmen in this 1868 picture from Harper’s Weekly.

Library of Congress

“The Freedmen’s Bureau is a story that needs to be told. All Americans would benefit by it. African Americans would greatly benefit by it. It comes as Abraham Lincoln’s greatest gesture, certainly his final gesture before he was murdered. Some four million slaves were set free and they would not have any place to stay, any place to sleep, or any food to eat had it not been for the concept of the Freedmen’s Bureau. When you know your background then your foreground pretty well takes care of itself. When you know where you’re coming from then you can design where you are going.” - Rev. Dr. Cecil L. Murray

The Civil War ended on April 9, 1865 with General Robert E. Lee’s surrender of the Confederate Army to the Union Army. The country was in complete chaos. How could a country that was so strongly divided mend itself into one cohesive unit? What would happen to over 3.5 million enslaved persons who have now been freed?

Before the war was even near an end, President Abraham Lincoln wrote the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862 and it went into effect on January 1, 1863. This act was not enforced until the South lost the War and most enslaved persons were not freed until late 1865. As one can imagine, the South’s defeat motivated stronger racial sentiments towards African Americans.

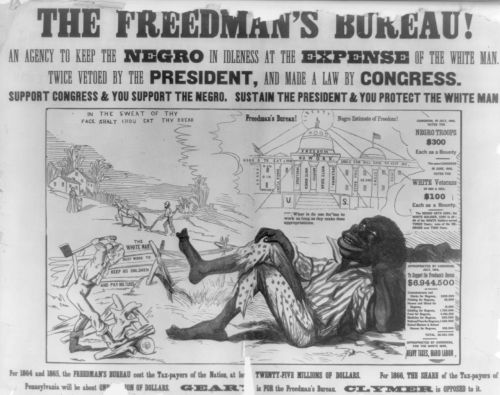

Photo: One in a series of racist posters attacking Radical Republicans on the issue of black suffrage, issued during the Pennsylvania gubernatorial election of 1866. Library of Congress.

Fortunately, during the Reconstruction Era, one essential organization provided support to the newly freed enslaved persons and poor whites of the South. In March of 1865, an act of Congress established within the War Department, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. President Lincoln signed the act into law, and with the consent of the Senate, appointed a commissioner for the Bureau to be in charge of all affairs relating to freedmen.

General Oliver Otis Howard, the first and only commissioner of the Bureau, sympathized with how enslaved persons were treated. He knew going into this position that the Bureau was on a time frame, so he did his best to establish programs that would extend beyond the Bureau’s existence.

In general, the Freedmen’s Bureau intended to help blacks and whites with the transition from enslaved labor to citizenship. They provided:

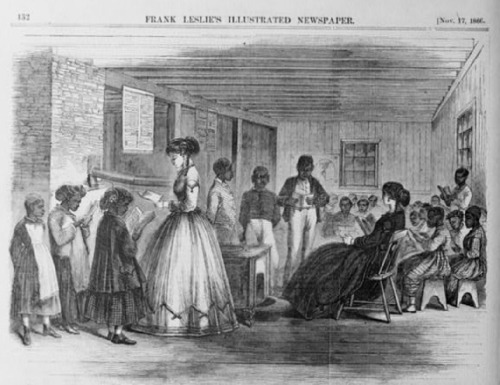

Photo: The Misses Cooke’s school room, Freedman’s Bureau, Richmond, Virginia, 1866. Library of Congress

The Bureau lacked military and monetary support to fully implement their first few efforts. They were most successful in the establishment of schools and record keeping. Along with the American Missionary Association, wealthy philanthropists, and black denominations of churches, the Bureau was able to educate African Americans, who once were denied that right.

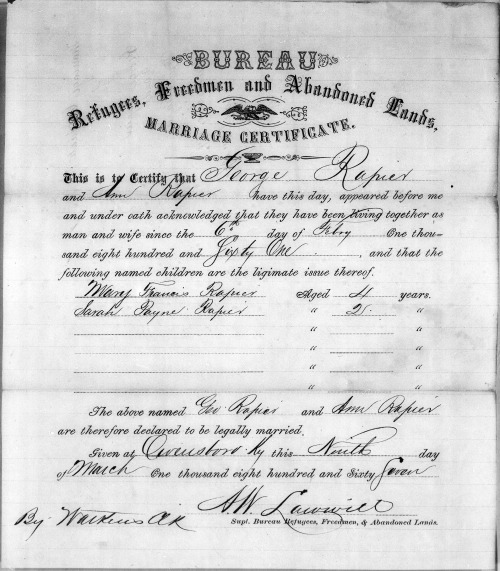

Photo: Marriage Certificate, The Freedmen’s Bureau records.

The most visible success of the Bureau and their associates was the establishment of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Howard University, Fisk University, and Morehouse College are some of the most well-known HBCUs that were established during Reconstruction. The Freedmen’s Bureau established a school system in addition to going above and beyond to help all those who needed it— including freedmen, women, children and poor whites.

With the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau, for the first time in U.S. history, the names of formerly enslaved individuals were systematically recorded and preserved for future generations. Unfortunately, the majority of those records were lost.

This week we will announce The Freedmen’s Bureau Project. This initiative is helping African Americans reconnect with their Civil War-era ancestors. Join us in restoring thousands of records, and to begin building your own family tree.

By Shannon, Social Media Intern, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

James Brown’s signed guitar. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

See more of our James Brown collection in our Through the African American Lens:Selections from the Permanent Collection exhibition.

Photo: Slick Rick with Timothy Burnside.

Join us tomorrow to talk #blackmusicmonth on Twitter! Hosted by Dwan Reece, Curator of Music and Performing Arts, National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and Timothy Burnside, NMAAHC Curatorial Museum Specialist, the chat will focus on the music collections at NMAAHC in honor of African American Music Appreciation Month (also known as Black Music Month).

Reece is curator of the museum’s permanent exhibit, Musical Crossroads, that will reflect African American music making from its earliest manifestations to the present day. Musical Crossroads aims to validate the influence of African American music on American culture and provide visitors with the framework to appreciate African American music as a vehicle of cultural survival and expression, musical innovation and social progress. Through the exhibition’s content, visitors will develop an understanding of the crucial role African American music-making has played in determining the aesthetic and cultural impact of American music production on the domestic and global stage.

In this piece from WAMU, Burnside details her job collecting musical objects for the museum:

“I think it really smashes a lot of ideas about what the Smithsonian does and what it’s supposed to do,” Burnside says of the African-American museum’s growing hip-hop collection. “I think a lot of people put the Smithsonian museums into this kind of realm of long-gone history, and way, way, way back is how we can understand things and learn from our distant past. And that’s not the case.”

The chat will be held from 2 p.m. - 3 p.m. on June 10th and you can follow the conversation on Twitter to participate.

Please send all of your music related questions to us using #asknmaahc.

More about African American Music Appreciation Month:

African American Music Appreciation Month was founded in 1979 by Dyana Williams, Kenny Gamble, and Ed Wright. The month-long celebration dedicated to highlighting the achievements of African Americans to music. The celebration was formally recognized by the United States in a reception hosted by President Jimmy Carter on June 7th, 1979.

Can’t make the chat? Stay tuned as we highlight some of our favorite African American musicians — from funk to hip-hop, and their contributions to music throughout June.

By Lanae S., Social Media Specialist, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

June 8th is National Best Friend Day! Please enjoy a few images from our collection that include photos of friends and sibling groups.

You can find additional images in our Collections Search Center.

Photo: Table Bay in the 1790’s, Thomas Luny (1759-1837). Depiction of Table Bay, the port of the city of Cape Town, South Africa. The São José slave ship was planning to stop in the port before wrecking. Credit: Iziko Museums collection.

Today the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in collaboration with Iziko Museums of South Africa, and The George Washington University will announce the findings of an international research partnership.

The Slave Wrecks Project provides new knowledge on the Transatlantic Slave Trade, focusing on the São José slave wreck, discovered off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa.

In 1794, the São José, a Portuguese slave ship, was wrecked near the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. Destined for Brazil, the ship was carrying more than 400 slaves from Mozambique when it struck a rock and began to sink. The crew and some of those enslaved were able to make it safely to shore, but tragically, more than half of the enslaved people aboard died in the rough waters.

The São José left Lisbon April 27, 1794, to purchase slaves in Mozambique, with the intent to continue on to Brazil. The Cape of Good Hope in South Africa had long been supplied with enslaved people from parts of East Africa, but beginning in the 1790s, East Africa also became a significant source of slaves for the Brazilian sugar plantations. The São José was one of the earliest voyages of the slave trade between Mozambique and Brazil, a massive trade in human beings, which continued well into the 19th century. More than 400,000 East Africans are estimated to have made the journey between 1800 and 1865, transported in inhumane conditions in voyages that often took two to three months; many did not survive the trip. For many years Cape Town prospered as a way station for this trade before ships began their long trans-Atlantic journey.

Photo: Copper fastenings and copper sheathing recovered from the São José slave ship wreck. The copper fastenings would have held the structure of the ship together and the sheathing provided exterior protection for the vessel. Credit: Iziko Museums.

The Slave Wrecks Project (SWP), is a collaborative effort between the NMAAHC, Iziko Museums, the South African Heritage Resources Agency, the George Washington University and a core group of international partners, uses slave shipwrecks to investigate the impact of the slave trade on world history. The still-developing story of the São José represents the work of researchers and scholars from Mozambique, South Africa, Portugal, Brazil and the United States. SWP has now amassed enough information in Cape Town, Mozambique, Portugal and Brazil to tell a story of the ship owners, captains and voyage of the São José. But what is most important is what can now be said about the enslaved Africans who perished in that shipwreck. The São José is the first known shipwreck to be identified, studied and excavated that foundered with enslaved Africans on board.

Photo: Underwater archaeology researchers on the site of the São José slave ship wreck Credit: Iziko Museums.

The identification of the São José ship off the coast of South Africa provides an unparalleled opportunity for SWP to diligently excavate, conserve and prepare authentic objects of the trans-Atlantic slave voyage. The São José is also highly significant because it represents one of the earliest, experimental voyages that brought East Africans into the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Photo: Underwater archaeology researchers identify guns on the wreck of the São José. Credit: Iziko Museums.

The selection of artifacts retrieved from the São José loaned by Iziko Museums and the government of South Africa for display at the inauguration of the National Museum of African American History and Culture will provide visitors with uniquely powerful and authentic symbols of the Middle Passage. These objects and the story they tell will provide tangible and intimate touchstones through which people from around the world will be able to reflect upon and grapple with a trade that spanned the globe, shaped world history and through which millions tragically lost their lives.

Photo: Underwater archaeology researchers on the site of the São José slave ship wreck Credit: Iziko Museums

April 27, 1794—The São José, a ship owned by Antonio Perreira and captained by his brother, Manuel Joao Perreira, left Lisbon for Mozambique with more than 1,400 iron ballast bars in its cargo. Seeking new markets, it is one of the first attempts by European slave traders to bring East Africa into the broader trans-Atlantic West African trade.

Dec. 3, 1794—São José, laden with more than 400 captive Mozambicans likely from the interior of the country, set out for its destination: Maranhao, Brazil.

Dec. 27, 1794—Caught in variable winds and swells off the coast of Cape Town, the São José ran into submerged rocks in Camps Bay about 100 meters (328 feet) from shore. A rescue was attempted, and the captain, crew and approximately half of those enslaved were saved. The remaining Mozambican captives perished in the waves.

Dec. 29, 1794—The captain submitted his official testimony before court, describing the wrecking incident and accounting for the loss of property, including humans. Surviving Mozambicans were resold into slavery in the Western Cape. Apart from the court documents and scant reports throughout the years, the incident of the São José and the fate of those 200 enslaved Mozambicans passes out of public memory.

After 1794—The Portuguese family who owned and operated the São José continued their international slave trade and make several complete voyages bringing captive Mozambicans to Northeast Brazil where they are sold into slavery on plantations in and near Maranhao.

Photo: Site of the São José slave ship wreck near the Cape of Good Hope.Cape Town, South Africa Credit: Susanna Pershern, U.S. National Parks Service.

1980s—Treasure hunters discovered the wreck of the São José and mistakenly identified it as the wreck of an earlier Dutch vessel.

2010–11—SWP discovered the captain’s account of the wrecking of the São José in the Cape archives. Combined with the treasure hunters’ report from the 1980s, new interest developed on the site. Copper fastenings and copper sheathing indicated a wreck of a later period, and iron ballast—often found on slave ships and other ships as a means of stabilizing the vessel—was found on the wreck.

2012–13—SWP uncovers an archival document in Portugal stating that the São José had loaded iron ballast before she departed for Mozambique, further confirming the site as the São José wreck. The SWP later uncovers a second document in Mozambique confirming the sale of a Mozambican on to the São José. Full documentation of the wreck site begins in 2013. Complementary archival work continues at an advanced stage and is supplemented by additional work in Europe, Brazil and Mozambique.

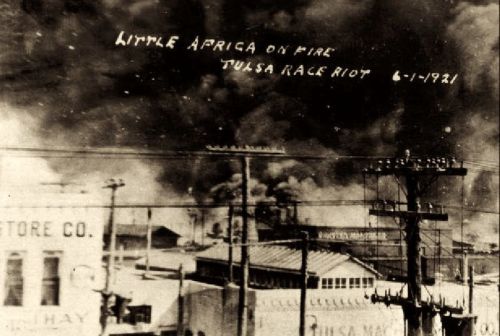

Photo: Little Africa on fire. Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921 This photo was taken from on top of the Santa Fe Freight office at 1st St. and Elgin Ave., showing the fires on Archer towards Greenwood. Postcard in the collection of McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa.

Hidden along the north side of Tulsa, Oklahoma was an area known as the Greenwood District. It was established in 1906 by O.W. Gurley, a black entrepreneur from Arkansas who bought 40 acres of land along Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa. Greenwood was the section of Tulsa that was regulated to African Americans when Jim Crow laws were established. Greenwood was a successful community of more than 15,000 and included several groceries, two independent newspapers, two movie theaters, nightclubs, and numerous churches.

The thriving community led Booker T. Washington to call Greenwood The Negro’s Wall Street and the moniker stuck.

On Monday, May 30th, 1921, a black man was jailed after he was suspected of the attempted rape of a white woman. In response, more than 10,000 Ku Klux Klan members attacked the black residents of Greenwood from May 31st - June 1st, 1921.

Photo: National Guard and wounded during 1921 Tulsa race riots.

During the 16 hour Tulsa Race Riots at least 35 city blocks, containing over 1,200 homes, were destroyed by fire. Some experts estimate that thousands of men, women, and children were killed even though the official count was 39.

In 1996, Oklahoma had the state legislature commission a report to establish the historical record of the events. The Oklahoma state legislature passed the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act in 2001 which provided for more than 300 college scholarships for descendants of Greenwood residents, mandated the creation of a memorial to those who died in the riot, and called for efforts to promote economic development in Greenwood.

Written by Lanae S., Social Media Specialist, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

On Tuesday, the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in collaboration with Iziko Museums of South Africa, The George Washington University, South African Heritage Resource Agency, US National Park Service – Submerged Resource Center, Diving With A Purpose, and African Center for Heritage Activities (ACHA) will announce the findings of an international research partnership.

The #SlaveWrecks Project provides new knowledge on the Transatlantic Slave Trade, focusing on the São José slave wreck, discovered off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa.

Photo: Iron blocks of ballasts recovered from the wreck of the São José, a Portuguese slave ship, on which they were used to offset the weight of the human cargo. Iziko Museums.

From the The New York Times:

“I wanted to find a way for people to remember all those nameless people who died crossing that Middle Passage.“ - Director Lonnie Bunch

Read the in-depth story behind the #SlaveWrecks project.

Watch this video to hear the story of the São José slave wreck and see underwater dive footage. You will hear firsthand from many partners of the #SlaveWrecks Project.

The URL you requested could not be found.